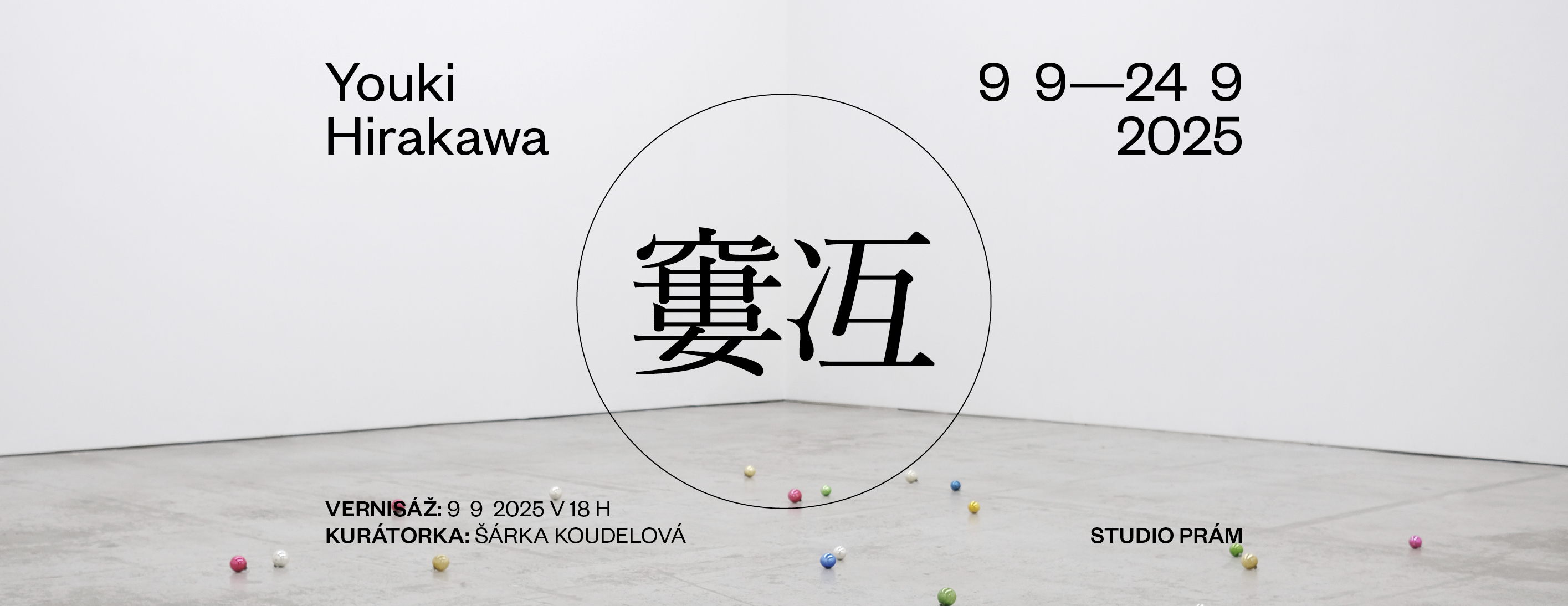

Youki Hirakawa: 窶冱

exhibition: 10. 9. – 24. 9. 2025

The title of Youki Hirakawa’s exhibition consists of two letters that cannot be precisely translated or pronounced. It is a combination of archaic symbols from the Chinese characters, which repeatedly appear when translating text from Japanese to English using automatic translation tools, and then copying it from a ChatGPT interface into Gmail. This systemic distortion is an example of the phenomenon known as mojibake—a string of unreadable characters that arises from incorrect encoding interpretation. This “in-between space,” where two cultural systems meet, is also a frequent area of artistic exploration for Youki Hirakawa. Despite all human effort, incredibly sophisticated technology, and the global virtual and gastronomic environment, intercultural contact still runs into errors in encoding, mutual prejudice, and food intolerances.

The physical and conceptual centerpiece of the exhibition is an installation made from used milk cans, titled Intolerance. These seemingly “innocent” objects can, through Youki’s interpretive coding, be read as an emblematic reminder of postwar Japan and the onset of American influence on Japanese society. Before World War II, cow’s milk was not a regular part of the Japanese diet. After Japan’s devastating defeat by the Americans, this gap in the market was quickly filled by the imported dairy lobby. New cattle farms and dairy facilities were accompanied by an ongoing campaign promoting the importance of drinking cow’s milk daily—a campaign that persisted despite the genetic unreadiness of the population, specifically the historically widespread absence of the enzyme necessary for digesting lactose. The milk cans thus become a form equivalent to the bombs dropped by Americans on the Japanese people, and, in a metaphorical sense, a reminder of the “exploder” it has become for their digestive systems.

Preceding this symbolically and conceptually rich dairy installation is the scent of seaweed, arranged by Youki into a flat surface that serves as a European analogy for Asian lactose intolerance. Euro-American digestive systems, in contrast, do lack the enzymes needed to fully digest seaweed. The dark green surface also serves to Youki as a marker of humidity differences between the continents. Over the course of the exhibition, its perfection is gradually disturbed by bent corners, creases, and warping—reactions to the environment of the exhibition space. The array of symbols and cultural and historical references is rounded out by a playful installation titled Easter, based on the similarity between the name of Christianity’s most important holiday and the cardinal direction that simultaneously dogmatizes Eastern societies.

Youki’s creative approach could be symptomatically described as a language that helps decipher mojibake. He examines everyday items that have become politicized or, through their universal emotional charge, have transformed into their own kind of code—like Budweiser beer. Although the name is actually a toponym as it originally refers to a place of origin, the idealized qualities of the beer have become a code for its character and marketing. This outer alignment of characters, masking a contradiction in internal coding, is presented through two different, yet similarly colored cans—always perfectly dewy, thanks to Youki.

The project is implemented with financial support from City of Prague and State Fund of Culture of the Czech Republic.